This timeline of events over a single week in July 1995 has been reconstructed using witness statements, documents and other evidence exhibited in trials before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

The events in Srebrenica in July 1995 were foreshadowed in two documents created as early as 1992. The plans contained therein were implemented step by step in the years to follow.

At the 14th session of the Assembly of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 16 May 1992, the deputies adopted six Strategic Objectives of the Serbian people. The Strategic Objective No.3 called for the elimination of 'the border along the Drina river which now separates the Serb states' - the Republic of Serbia and Republika Srpska.

On 19 November 1992, General Ratko Mladić, commander of the BSA (Bosnian Serb Army) Main Staff, signed his Directive No. 4, which set out the means to be used to implement the third Strategic Objective: 'Inflict as many losses on the enemy to force him to leave the areas of Birač, Žepa and Goražde' in eastern Bosnia, together with the Muslim civilian population.

In a bid to implement Strategic Objective No.3, the army launched a series of military actions based on Directive No. 4 during the winter of 1992/93. As a result, tens of thousands of Muslims who had been ethnically cleansed from their homes in Muslim villages in the Drina river valley were forced to seek refuge in the enclaves of Srebrenica, Žepa and Goražde.

Faced with a dire humanitarian situation in the Srebrenica enclave, where around 40,000 refugees, expelled from their homes, had fled to safety, on 16 April 1993 the UN Security Council adopted its Resolution 819 declaring Srebrenica the first 'safe area' in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On 8 March 1995, Republika Srpska president Radovan Karadžić signed Directive No. 7, ordering his troops to 'create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the inhabitants of Srebrenica and Žepa.”

On 6 July 1995, the commander of the BSA Drina Corps ordered his troops to launch Operation Krivaja '95, which was the code name for an all-out attack on Srebrenica. Mladić’s troops encountered almost no resistance from the BH Army, the UN Dutch Battalion stationed in the enclave and NATO war planes. By 10 July, BSA soldiers were on the outskirts of Srebrenica and nothing could stop their advance into the undefended 'safe area'.

Selection of Exhibits

TimelineA week in July

11 July

The panicked inhabitants of the enclave, mostly women, children and the elderly, seek shelter in the UN Dutch Battalion base in Potočari.

Around 15,000 men, soldiers and civilians alike, gather in the villages of Šušnjari and Jaglići.They form a column, intending to break through to Tuzla, in BH Army-controlled territory.

During the afternoon of 11 July, General Ratko Mladić triumphantly enters the eerily empty town of Srebrenica and announces in front of TV cameras that there will be 'revenge against the Turks'.

The same evening, Mladić meets with Dutch Battalion commander Thom Karremans in the hotel Fontana and vents his anger on him.

Later that night, Karremans returns to the hotel Fontana with Nesib Mandžić, a teacher who has reluctantly agreed to represent the 25,000 refugees sheltering in Potočari. Mladić offers Mandžić and the refugees a stark choice: to 'survive or disappear'.

12July

At another meeting at the hotel Fontana, Mladić gives Ćamila Omanović, Ibro Nuhanović and Nesib Mandžić, who represent the refugees, the same choice he offered Mandžić the previous day: to "survive or disappear".

The first buses and trucks arrive in Potočari at noon to transport the refugees to territory controlled by the BH Army. Only women, children and the elderly are allowed to board the

vehicles. Men of military age are separated, and taken to a building called the White House, across the road from the UN base. Before entering the house, they are made to hand over their personal belongings and identification.

UNPROFOR soldiers escort the first refugee convoy to the demarcation line, but then the Serb forces seize the UN vehicles, weapons and equipment. As one of them recounted, they were forced to return to their base 'in our underwear'. The Dutch Battalion command decides not to escort any more convoys.

Mladić visits the refugees in Potočari, assures them they will come to no harm and that those who want to will be evacuated. He warns parents to look after their children so they wouldn't be lost.

The Dutch soldiers find the bodies of nine men behind the White House who have been killed. A Dutch lieutenant photographs the dead bodies, but the photographs have never come to light: the film was purportedly destroyed as it was being developed in a military lab in the Netherlands.

13 July

The deportation of women and children from Potočari continues. They are taken away in convoys which are no longer escorted by the UN.

The column moving through the woods is exposed to constant artillery and anti-aircraft fire. Serb forces set up ambushes along its route. Using equipment stolen from the UN, the Serb soldiers masquerade as the peace-keepers and call on the people in the column to surrender. Those who have surrendered or been captured are gathered in a meadow near the village of Sandići and on the football pitch in Nova Kasaba.

Sixteen men from the column who have been captured near Konjević Polje are shot on the banks of the Jadar river.

Around 1,000 prisoners from the Sandići meadow and other sites where they were gathered are now moved to the warehouse of the agricultural cooperative in Kravice. Their massacre begins on the afternoon of 13 July. The killings will continue into the morning hours of the next day.

Around 4,000 prisoners are taken to Bratunac and put in the elementary school building, the hangar, the football pitch and other facilities. Those who cannot be crammed into makeshift

detention centres spend the night in buses parked throughout the town centre. During the night dozens of prisoners in the school, the hangar, on the football pitch and in the buses are killed.

14 July

After spending the night in the detention facilities in Bratunac and the buses parked in the town centre, thousands of prisoners are moved to locations in Zvornik municipality.

Around 1,000 prisoners who have been detained for a short time in the school in Orahovac are executed in a nearby meadow, next to the railway tracks. Three prisoners survive.

Around 1,000 prisoners held in the elementary school in Petkovci are executed during the night of 14 July 1995 at a reservoir dam nearly. Two men survive.

15 July

At least 500 prisoners held in the elementary school in Ročević are taken to the execution site at the Kozluk gravel pit. There are no survivors.

16 July

From 10 a.m. to around 4 p.m., between 1,000 and 1,200 prisoners are taken in groups from the elementary school in Pilica to the military farm in Branjevo. They are summarily executed. Three prisoners survive.

At least 500 prisoners are detained and killed in the Cultural Centre in the village of Pilica. There are no survivors.

Sometime after 16 July

In late July 1995, at Godinske bare near the village of Trnovo, south of Sarajevo, members of the Scorpions unit executed six Muslim men and boys who had been brought almost 200 kilometres from the Srebrenica area.

The footage showing the cruel abuse of the prisoners and their execution - they were shot in the back from automatic weapons - circulated among the Scorpions and their fans in Serbia for ten years as a macabre home video. It finally ended up in the hands of prosecutors in The Hague. In June 2005, the recording was shown at the trial of Slobodan Milošević, together with documents which proved that the Serbian Ministry of the Interior had dispatched the Scorpions to Bosnia and Herzegovina to support the Republika Srpska police and military on the Sarajevo front.

The ICTY’s Srebrenica investigation is often described as the largest-scale criminal investigation in post-war Europe; some say it is the most comprehensive investigation of its kind in the 20th century. This may well be the case, as evidenced by at least three criteria.

First, the scale of the crimes and the number of victims: at least 7,000 people were killed and 25,000 were forcibly removed from their homes.

Second, the size of the crime scene: 70 kilometers on a North-South axis and 40 kilometers on an East-West axis, making up a total surface area of 2,800 square kilometers.

Third, the duration: launched in July 1995 and continuing through 2014, this investigation will continue, as far as the ICTY is concerned, until the last trial of persons charged with the Srebrenica crimes is over.

Selection of Exhibits

The first exhumations of the mass graves found at some of the execution sites such as Branjevo, Cerska and Orahovac started in July 1996. The remains of about 500 victims were found in these graves. However evidence was also uncovered of a secret operation carried out in the fall of 1995 to cover up the crimes: the mass graves were dug up and the bodies moved to other locations, where they were reburied in so-called secondary graves.

Crucial to the effort to find the secondary graves were aerial photos given to the Prosecution by the US Government. Taken in the fall of 1995, these photos show significant disturbance to the terrain in a number of locations in some sites. ICTY investigators used these photos to locate about 40 secondary mass graves.

Selection of Exhibits

ICTY investigators identified the first survivors of the Srebrenica mass executions during their field missions to Tuzla in July and August 1995. By the end of 1995, the investigators had taken statements from about a dozen men who claimed they had survived the mass executions.

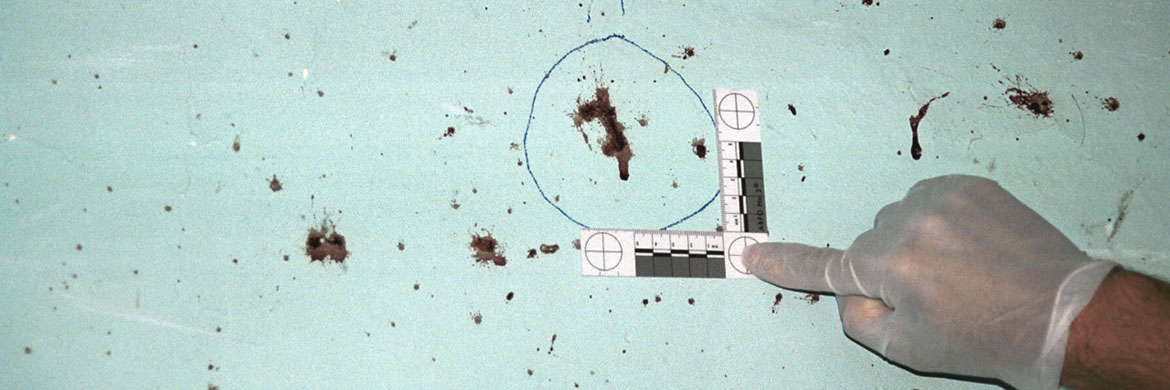

In order to verify their claims, in 1996 investigators visited the areas the survivors had described. First, they found the buildings in which the survivors had been detained (mostly schools in the Bratunac and Zvornik areas). Then they found the actual execution sites: the warehouse in Kravica, the Petkovci dam, the Branjevo farm, the road in the Cerska valley, the banks of the River Jadar...

Tragically, no one survived the mass executions at the gravel pit near Kozluk and in the Pilica Culture Hall.

Selection of Exhibits

Three of the 15 Bosnian Serb Army servicemen charged with the Srebrenica crimes pleaded guilty.

The first of them, a soldier in the 10th Sabotage Detachment Drazen Erdemovic, confessed to the crimes even before he was indicted. In an interview with a French newspaper, Erdemovic described in detail his involvement in the execution of about 1,200 captured men at the Branjevo farm on 16 July 1995. With that interview, in effect, he wrote his own indictment.

The other two ‘penitents’: Major Momir Nikolic and Captain Dragan Obrenovic, made a plea bargain with the Office of the Prosecutor after their indictment and arrest, but before trial.

As the Tribunal’s Srebrenica investigation progressed, the number of identified hostile, insider witnesses grew.

Their names and roles came to light in the documents seized in various BSA commands, such as personnel lists for various units or work logs for the use of heavy vehicles and earth-moving machinery.

They were interviewed by the OTP investigators, many as suspects and in presence of their lawyers.

Those people, former Bosnian Serb soldiers, policemen and officials from the civilian authorities in the Srebrenica area, for the most part came to The Hague to testify when they were compelled to do so by subpoena.

Once in court, bound by the solemn declaration to speak the truth, they had to tell the judges what they had done, seen or heard as the events in Srebrenica unfolded.

It is not the task of the Tribunal to determine the role and responsibility of the international community for the Srebrenica tragedy; its mandate is to determine the criminal responsibility of individuals charged with serious violations of international humanitarian law.

The role and responsibility of the Dutch ‘blue helmets’ and the French generals at the helm of UNPROFOR have been dealt with in parliamentary enquiries in the Netherlands and France. The Dutch Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) has also investigated that aspect of these events. A comprehensive report by the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, was published in 1999. In that report, Annan concluded, “The tragedy of Srebrenica will haunt our history forever.”

The powerless eyewitnesses to the fiasco of the international community in Srebrenica - the Dutch Battalion commanders, UN military observers, humanitarian workers...- testified about their inability to do anything to stop the horror unfolding before their eyes.

Selection of Exhibits

“For the Muslim community of Eastern Bosnia, Srebrenica is a tragedy, a tragedy of such proportions that my words here today can only begin to convey to you the true magnitude of that crime. But the greatest tragedy of Srebrenica is no longer found in the dead, because their suffering is over. We cannot forget the families left behind, those people who have been condemned to live their lives without their fathers, without their husbands, their brothers, their sons, their cousins, their neighbors, their community. There is too much pain, there is too much loss for any of us to truly comprehend the nature and scope of this crime committed against the Muslim community of Eastern Bosnia.”

Peter McCloskey, Prosecutor

Opening statement in the case "Blagojevic and others" 14-05-2003

Selection of Exhibits

Over the course of a few days in July 1995, following the fall of Srebrenica, thousands of Bosnian Muslim males were detained in deplorable conditions.

The men endured a brief but horrific period of detention in various public buildings, mainly schools. The facilities were woefully inadequate; the men were taunted along ethnic lines and largely denied food and water. An atmosphere of terror was maintained through beatings and sporadic executions. Their spirits broken, the Bosnian Muslim men were taken for execution. Some were blindfolded and their hands were tied, and at one detention site they were given a final cup of water. Then they were transported to nearby locations, and shot.

In parallel to these mass executions, Bosnian Muslim women, children and the elderly were transferred out of this part of Eastern Bosnia. In the context of the war in the former Yugoslavia, and in the context of human history, these events are arrestive in their scale and brutality.

Summary of Trial Chamber’s factual findings in "Popovic at al" Judgment